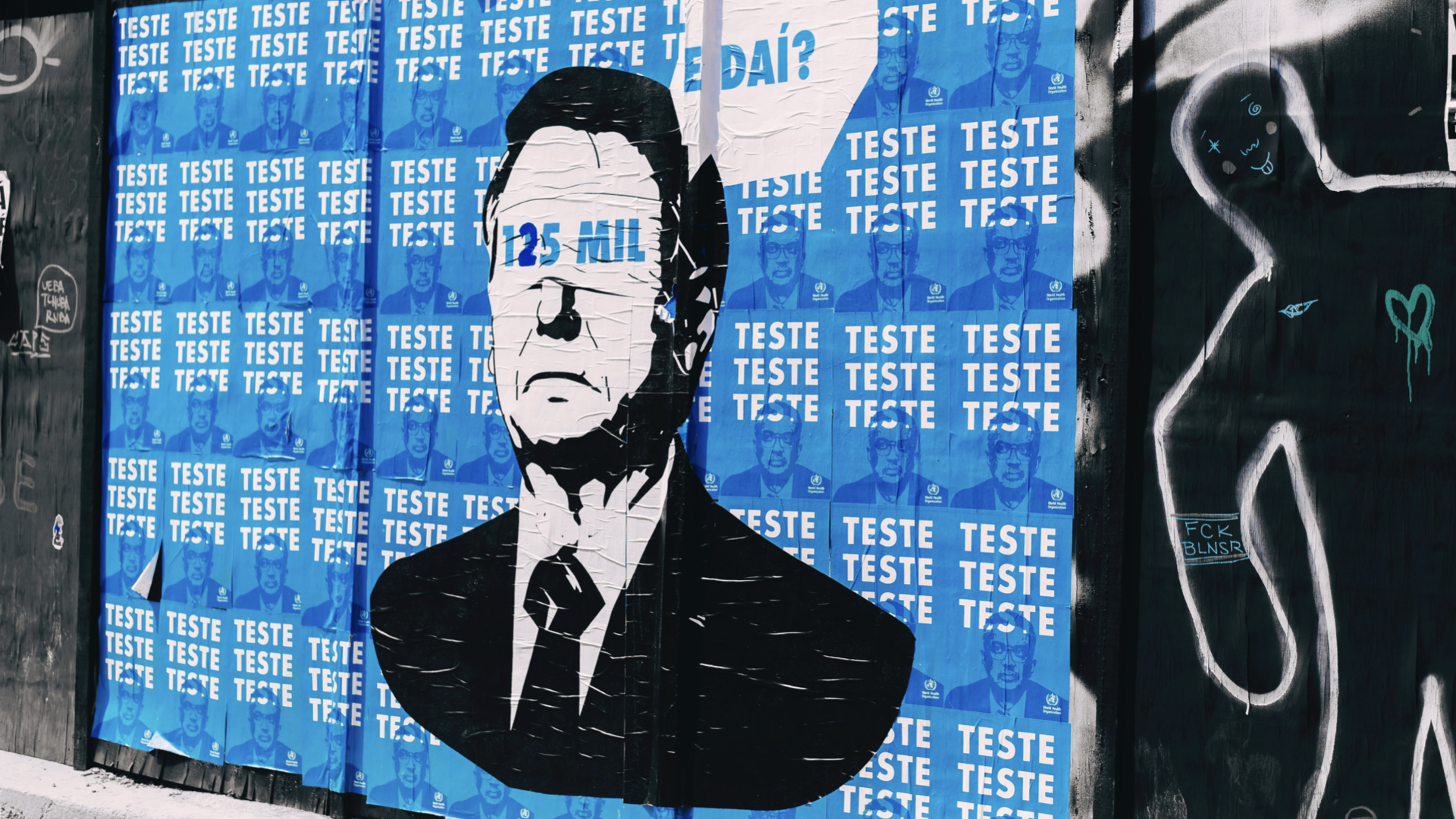

Tens of thousands of Brazilians protested in the streets of 40 cities on July 3, voicing their disapproval of President Jair Bolsonaro. One day earlier, Brazil’s highest court had ordered an investigation of Bolsonaro’s involvement in a possibly corrupt deal to import COVID-19 vaccines from India. Bolsonaro—who’s repeatedly railed against homosexuality, endorsed political violence, and lavished praise on the former U.S. president Donald Trump—came to power in 2018, as populists with authoritarian aspirations strengthened their control over democracies around the world, including Jaroslaw Kaczynski in Poland, Narendra Modi in India, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey. Does Bolsonaro’s weakened position show new vulnerabilities in authoritarian populism globally?

According to Oliver Stuenkel, a Brazilian professor of international relations at the Sao Paolo-based Getulio Vargas Foundation, Bolsonaro is on the defensive because of multiple corruption allegations and Brazil’s tattered economy. As Stuenkel sees it, populists worldwide have fumbled their handling of the pandemic; Brazil has the second-highest official death toll from COVID-19 and is on pace to pass the United States. Trump’s failures responding to the pandemic, for example, critically damaged his reelection chances, Stuenkel says. The keys to rolling back authoritarian populism, in Stuenkel’s view, are free media that can report on government performance and free elections that allow voters to change course when leaders fail to deliver.

Michael Bluhm: How do Bolsonaro and Brazil fit into the global rise in authoritarian populism?

Oliver Stuenkel: Brazil is in every text on this subject because of how explicitly Bolsonaro embraced authoritarian ideas as a candidate, which makes Brazil a bit different from countries like Turkey, where you initially did have support even from the international community [for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan], and then these leaders slowly became more authoritarian.

Bolsonaro sensed in 2018 a unique opening, because you had disenchantment not only with political elites, but with democracy. You don’t have somebody like Bolsonaro emerge in a healthy democracy. We tend to focus on individuals and say, This person is key in understanding the erosion of democracy. But somebody like Bolsonaro doesn’t have a shot at winning an election in Sweden, or Switzerland, or Uruguay.

Brazil’s democracy is a young democracy. Our constitution is from 1988. We had the first direct presidential election in ‘89. This is something that most Brazilians can remember.

Since Brazil crashed out of the World Cup in 2014, which it had organized, things have deteriorated economically, politically, and there was a sense that democracy hadn’t fulfilled the promises made in the late ‘80s and early 1990s.

That’s different from the United States. That explains why someone like Bolsonaro could emerge and say, I want things to be like during the dictatorship, which took place in Brazil from 1964 to 1985, when people didn’t have political rights and where, by virtually all measurable standards, life was not better.

He could create this discourse of nostalgia, which got people to opt for a radical outsider with no credible effort to address any of the challenges the country was facing.

On top of that, you have a sense that political elites have failed the country and nobody could take the country out of the abyss. Therefore, an outsider was needed, even though that person wasn’t actually an outsider—Bolsonaro had been in Congress, doing very little, for 28 years, but he was able to project himself as something like that.

We must explain the threat to Brazil’s democracy in the difficulties that successive democratic governments have had to offer public goods to many of its citizens, which explains this sense of, Well, perhaps we should give a chance to somebody who has this authoritarian discourse, because we have nothing left to lose.

Bluhm: How do those sentiments among Brazilians compare to the sentiments of citizens in other countries that have elected populists?

Stuenkel: One of the distinctive elements of Brazil is that there was a desire to have somebody who could offer direction, protection, and order, who could take swift action. Even if he or she made mistakes, at least we have decisions being made.

In some countries where authoritarians have emerged, people feel that democracy is inefficient and authoritarians can implement ideas and projects faster, and deliver public services faster, even though the problem is that there are, in authoritarian regimes, fewer mechanisms to self-correct.

We tend to focus on individuals and say, This person is key in understanding the erosion of democracy. But somebody like Bolsonaro doesn’t have a shot at winning an election in Sweden, or Switzerland, or Uruguay.

This desire for strong leaders is something we did see in the United States, even though institutions were much stronger, and thus Trump, in the end, failed. But it’s something you can also see in India, where Modi projects himself as this masculine, strong leader. We see that in Hungary, in Turkey.

The military’s role is a bit different, because there was no military dictatorship in the United States. But, like in the Philippines, there is this sense among Bolsonaro supporters that the army can address problems in a more efficient and a better way, be it urban security, deforestation, education. One of the popular elements of Bolsonaro’s campaign was more military schools. It turned out that you can’t roll out military schools across the country—these are elite schools which receive massive amounts of public funding, and which, as a consequence, are better. But that’s not a model for a country of 228 million.

This fascination with military power has become visible in the Philippines, as well. This fusion of military and politics is in Venezuela and in other countries where the state is struggling to deliver—even in Mexico.

Then you have the emergence of people like Bolsonaro, who sell this idea that we can take the country back to some better past. You can see that even in the U.K.

That’s, in a way, a sign of progress. When Bolsonaro was saying, We want things to be like they used to, then that means that Black people are not at universities, not on airplanes, not at nice hotels. You have a social hierarchy which is much more conservative; you have no women in decision-making positions, you have a lot of repression against LGBT people.

There was a sense among a lot of conservative, evangelical voters, who said, This is going too far. I don’t know what my place is in this society. I suddenly have a Black boss. This is an anti-liberal backlash, which was visible in the United States, where there may have been some discomfort with the fact that the United States had a Black president. You had all these conspiracy theories whether he was born abroad—you didn’t have that with non-Black presidents. You can also see in some countries this backlash against a more inclusive politics, against falling inequality.

Finally, there is a sense of a reversal of expectations, visible in the United States after the financial crisis of 2008. Somebody like Trump came up because there were a lot of people who had hoped until 2008 that things would be one way, but they turned out another, and they realized that it would take many, many years—if ever—to improve their living standards.

In the U.S., India, and the Philippines, the traditional political elite had become detached. Somebody who would defy norms and say outrageous things would be appealing, because there was a sense that these traditional elites were far away. ... Hillary Clinton was unable to shed this accusation that she was detached. That’s something that populists can exploit very easily.

In Brazil, you had this commodity boom, and you had all these people who were working in kitchens or as bus conductors, and their kids would go to university in 2005 or 2010, and there was a real sense that things were changing. Then, after the commodity boom was over and after massive protests in 2013, you had a sense that a lot of these kids would drop out of university, because there’s no money left, and all these dreams are crushed, which contributed to a sense of despair and the willingness to make a radical bet.

One final thing: In the U.S., India, and the Philippines, the traditional political elite had become detached. Somebody who would defy norms and say outrageous things would be appealing, because there was a sense that these traditional elites were far away. Bolsonaro had violated environmental norms several times; he had been fishing in places where fishing was illegal. And he used that to say, Who hasn’t done that before? He said that we need to end the dictatorship of traffic fines. And people were like, That’s something I can relate to. Hillary Clinton was unable to shed this accusation that she was detached. That’s something that populists can exploit very easily.

Bluhm: How would you describe the similarities and differences between Trump and Bolsonaro?

Stuenkel: Bolsonaro clearly benefited from Trump’s rise, and he actively emphasized similarities after Trump’s election. That helped him promote an idea that people like Trump and Bolsonaro represented the future—and boosted the campaign’s confidence that they could win.

Trump and Bolsonaro have many similarities when it comes to a very personalistic, messianic style; strong emphasis on outsider rhetoric; very shallow on policy detail; very little interest in discussing specifics, but much more about relating to people’s grievances and projecting a broad yet vague vision of what they want the country to be; disdain for democracy; a premeditated, calculated way of mixing scandal, entertainment, threats, and bluster, which constantly keeps commentators and the political opposition off-balance, because you never know what’s going on or what he’s going to say next.

It’s all fascinating, so the media jumps at these tidbits of craziness. That’s part of the plan—a way to crowd out a cohesive, constructive, and respectful public debate about how to best address public-policy challenges.

A lot of the tactics create this distinction between “real” Americans, or “real” Brazilians, and “enemies” and “traitors.”

When it comes to fake news, Trump and Bolsonaro share a lot: the tactics of shaping public opinion, using social media to connect directly with voters, and setting up this weird symbiosis with the media, which involves attacking them as corrupt but also giving them a lot that they want—constant entertainment—making it very hard for them to report objectively.

The differences are that Bolsonaro has a typical Latin American pedigree. Despite all its flaws, the United States always was a democracy, even though early on not everyone could vote; it was never a military dictatorship.

When it comes to fake news, Trump and Bolsonaro share a lot: the tactics of shaping public opinion, using social media to connect directly with voters, and setting up this weird symbiosis with the media, which involves attacking them as corrupt but also giving them a lot that they want—constant entertainment—making it very hard for them to report objectively.

Bolsonaro, a former army captain, was in Congress for 28 years. He’s different, because Trump was really an outsider. He was very rich, but he was never fully accepted even in the business world.

Bolsonaro was very clientelist. He was reelected many times because he was there to defend the interests of policemen, active and retired military and reserve folks, fighting for more benefits or salaries. He was very much a political animal and an insider, a symbol of many things that are wrong with Brazilian politics. He had been in Congress for years making outrageous claims, saying that the military dictatorship should have killed more people.

Bolsonaro is part of that lineage of Caudillismo [the phenomenon of Latin American authoritarians emerging from the military], which makes him comparable to people like [the former Peruvian president Alberto] Fujimori, [the former Venezuelan president Hugo] Chavez, and others who have a much clearer path to breaking democracy. Trump didn’t have that, because the United States hadn’t, or hasn’t yet, lived through an actual rupture of democracy.

Bluhm: How did Bolsonaro handle the pandemic?

Stuenkel: Bolsonaro understood early on that the pandemic had the potential to affect Brazil’s economy and that, if the economy doesn’t go well, it’s very hard to maintain high approval ratings and to win reelection. As a consequence, he has sought to minimize the pandemic and create a dichotomy between being pro-lockdown, pro-social distancing or pro-economy, pro-jobs. And he was on the side of the economy and jobs.

You started having mayors, governors, and even the judiciary pushing for a robust response involving social distancing, and he fought those. It allowed him to say, If this creates an economic crisis, then we know whom to blame, and I’m not responsible.

In Brazil, that initially worked better than in the United States. The pandemic was probably one of the key reasons why Trump lost. His chances of winning reelection without a pandemic would probably have been higher.

When Trump lost, Bolsonaro was still fairly popular. He was able to navigate this very complex situation with high death rates, a collapse of the public-health system, and all the elements that would allow us to say that the government really mishandled the pandemic and embraced a denialist approach.

He maintained high approval ratings because of the differences between the United States and Brazil. Brazil has a much, much smaller percentage of people who can work remotely. It’s morally indefensible, but it’s smart from an electoral point of view, when he said, Those rich countries do social-distancing measures and all that. We can’t do that here, because Brazil is different. I know Brazil. I know the common man. And I know that the common man can’t work from home. If these public-health experts tell you to stay at home, it’s because they can stay at home. Only about a quarter of Brazil’s working population can work from home.

That, paired with a monthly, emergency-salary scheme to the poorest—which was massive—boosted Bolsonaro’s popularity. If the election had taken place in November, like in the United States, Bolsonaro would have gotten reelected easily, while Trump lost.

The pandemic was probably one of the key reasons why Trump lost. His chances of winning reelection without a pandemic would probably have been higher.

The denialist approach in Brazil worked for much longer than it did in the United States. Bolsonaro was much more radical. There was always this element of expertise that was still part of the American government. Fauci spoke on behalf of the U.S. government. These kinds of people were sacked in Brazil. Two ministers of health were sacked because they refused to endorse chloroquine as a treatment. Paradoxically, one of the reasons that allowed Bolsonaro to walk on water during the pandemic, electorally speaking, is that he went all the way.

Only now is that beginning to crumble—but he may still get reelected, because a lot of Brazilians have bought into Bolsonaro’s narrative that the pandemic is like the rain: A lot of people will get wet, but we just have to deal with it.

He’s losing some support now, but it’s not because of his mishandling of the pandemic. It’s because of corruption and a worsening economy. Bolsonaro was able to protect himself from the damaging effects of the pandemic better than Trump.

Bluhm: Bolsonaro is up for reelection in October 2022. Brazil’s Supreme Court has cleared former President Lula Ignacio de Silva to run for the presidency again, and polls show him leading Bolsonaro in a hypothetical vote. How are Bolsonaro’s reelection chances looking?

Stuenkel: Since democratization in Brazil, all incumbents who’ve sought reelection, got reelected. That’s above all due to the fact that Brazil’s public sector allows a president to direct public spending in a way that has a direct impact on his approval ratings. And Bolsonaro has done that, which allowed him to increase his approval ratings during the worst part of the pandemic, because of cash-transfer payments to the poorest. There’s a reasonable chance that he will maintain these cash-transfer payments until Election Day, in October 2022.

Governments have a lot of leeway to deliver a lot of stuff—a lot of roads and bridges and hospitals—prior to elections.

Even though Bolsonaro is on the defensive because of corruption investigations, you have more than more than 500,000 deaths, the economy is in shambles—it’s way too soon to count him out. His chances of reelection are around 40 to 45 percent.

Despite the chaotic response to the pandemic, most people will be vaccinated by mid-next year in Brazil. If there’s some sense that things are improving, that may help Bolsonaro.

He has a lot of options in his war chest: fake news, threatening that if he loses, he may not accept the result—which he is doing on a daily basis.

The denialist approach in Brazil worked for much longer than it did in the United States. Bolsonaro was much more radical. There was always this element of expertise that was still part of the American government. Fauci spoke on behalf of the U.S. government. These kinds of people were sacked in Brazil. Two ministers of health were sacked because they refused to endorse chloroquine as a treatment. Paradoxically, one of the reasons that allowed Bolsonaro to walk on water during the pandemic, electorally speaking, is that he went all the way.

Bluhm: You mentioned the economy. In recent conversations at The Signal, John Ikenberry and Minxin Pei said that the confrontation between democracies and authoritarian regimes will likely be decided by which regime type delivers better results for its citizens. If you look at authoritarian regimes, democratic regimes ruled by populists, and democracies not ruled by populists, how have they delivered for their citizens in pandemic response?

Stuenkel: The countries where populists rule have struggled more than countries that have listened to scientists, sought to develop strategies that are science-based, and to articulate a comprehensible response and to engage citizens—a public response about these very difficult tradeoffs of individual liberties and privacy, and public health and economy. Even though Trump is no longer in power, the United States and Brazil are the countries with the highest numbers of victims in the world.

Even though initially there was the sense that Asian countries were dealing better with this, some of that may have been related to the fact that these countries had other pandemics fairly recently and had rapid-response systems in place. These countries weren’t necessarily authoritarian. South Korea and Taiwan were quite effective initially, just like China—but with the advantage of having free media, which could point out shortcomings; where an open and transparent public debate could help advance discussion of how these tradeoffs should be implemented; and where voters had the chance to throw out leaders who weren’t delivering.

Trump’s defeat, in the context of the pandemic, is an argument for why democracies are better at responding to these kinds of situations, because voters preferred a course correction, which is not possible in authoritarian regimes. Those initial claims that dictatorships were better are now no longer as convincing. After the initial emphasis on vaccinating the American population, the United States is now emerging as a donor of vaccines.

Overall, the pandemic was bad for populists. It was good for moderates, for fact-based policy- policy-making, and neutral on the question of democracy versus autocracy.