Imagine a future when people work, study, and socialize indoors, unmasked, with none of it being in any way risky or unusual. As a historical matter, pandemics inevitably end. But the COVID-19 pandemic, with its continuous cycles of rising or lowering case counts, of lockdowns lifted and re-imposed, and with new virus variants on the horizon, isn’t showing a certain conclusion. Vaccines offer hope, but not everyone has access to them—or takes them when offered. COVID may feel like a thing of the past in some places, but it continues severely to impact much of the world and even parts of countries with substantial overall vaccination rates. Will it ever be time to switch to past tense in talking about the disease? When is a pandemic really over?

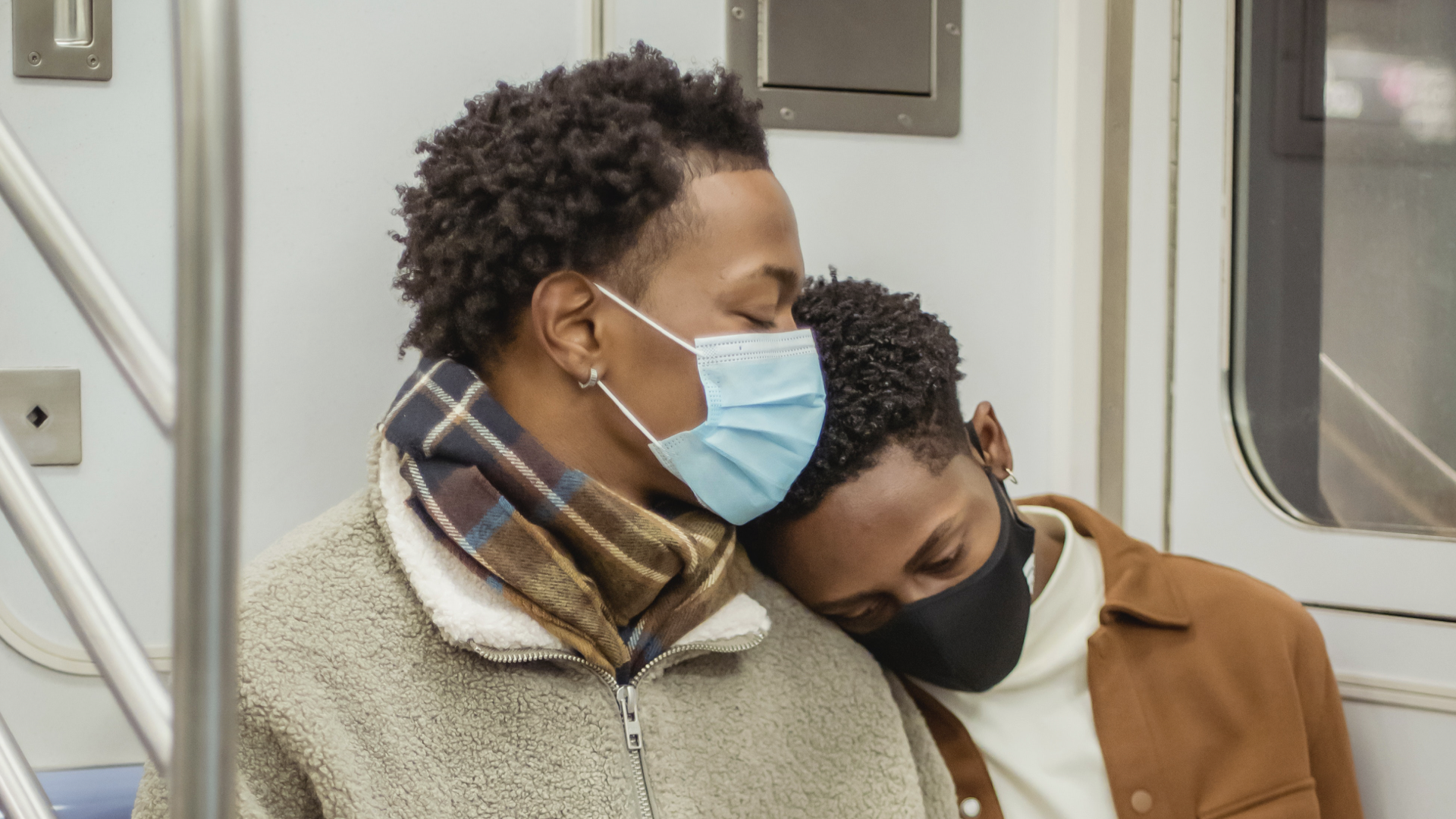

Timothy Caulfield, the Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy at the University of Alberta, suggests not to look for a “bright line that says, Now we’re post-pandemic,” but rather a more gradual process of returning to ways of life similar to pre-pandemic times. According to Caulfield, some practices, such as masking and refraining from shaking hands, may well persist beyond the pandemic itself. Given that pandemics are both infectious and global, as long as some of the world is still in crisis, even areas that COVID seems to be sparing may not be in the clear just yet. For the pandemic to end, Caulfield says, the virus doesn’t need to be eradicated fully. But it does need to be under control—which is why it can be dangerous when political leaders declare the pandemic over before public-health indicators support the idea.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: How will we know when it’s over?

Timothy Caulfield: From a public-health perspective, it’s over when we when don’t see any talk of public-health measures associated with the pandemic. It’s over when we stop worrying about vaccination uptake for this particular infectious disease, and about our vulnerable populations getting it. The reality is, some form of COVID is probably going to lurk for a long time. So declaring the pandemic over is going to be an arbitrary cultural moment, as opposed to an actual scientific finish line.

Bovy: So, for all the talk of post-lockdown life as the “post-pandemic” world, we’re certainly not there yet?

Caulfield: It isn’t over regionally, in most places in the world, and it certainly isn’t over globally, where we have nations struggling to get enough vaccines. There’s a lot more work to do. But it’s not even over regionally in North America. Countries like Canada that on the face of it look like they’re been very successful, with a relatively high level of double-vaccinated people, still aren’t there. We have to make sure that we have the vaccine distributed equitably across countries. This is particularly true in places like the United States, where you’re seeing a low vaccination uptake in some areas, resulting in pockets of infections, and also the suggestion that they are going to reintroduce measures like the mask mandate. The pandemic isn’t over from a public-health perspective, but most importantly, it’s not over culturally.

Bovy: Historically, how has the end of a pandemic been marked?

Caulfield: It’s not about the eradication of a disease. We’ve tried to eradicate diseases like polio. That’s not the goal here. We want to get herd immunity. We want to slow community spread to the point that this is no longer a public-health emergency. Those are different goals. One is much more ambitious than the others, and probably not achievable right now, especially given how infectious things like the Delta variant are. But the latter are achievable, especially in a number of countries.

Bovy: Is the expectation that COVID will become endemic, and therefore not a major cause for concern, or do new variants mean that unless it’s eradicated, the pandemic continues to some degree?

Caulfield: COVID-19 is likely to linger. But this highlights how incredibly valuable the vaccination process is, and why we can’t get complacent, even though it feels like we’re starting to exit the pandemic. What’s going to make it different in the future is the reality of hospitalization going down, so that won’t put as much strain on public-health systems. Even if we start to see blips, with more widespread vaccination we’re not going to see those excess deaths. People talk about natural herd immunity, but getting immunity through having had COVID isn’t necessarily a good thing, because of what we now know about long COVID [i.e., enduring symptoms, such as fatigue, shortness of breath, headaches, dizziness, or brain fog].

People talk about natural herd immunity, but getting immunity through having had COVID isn’t necessarily a good thing, because of what we now know about long COVID.

Bovy: Will COVID vaccines become an annual necessity, like flu shots, to prevent a resurgent pandemic?

Caulfield: The good news is, with the mRNA vaccines, it looks like the immunity is fairly impressive. But yes, I think we’re likely to see a need for boosters going forward.

Bovy: July 19 was “Freedom Day” in England, marking the end of most lockdown restrictions. To what extent can individual governments decide to declare an end to a pandemic, particularly given that pandemics are international crises?

Caulfield: Declaring the pandemic over doesn’t make it over from any scientific or public-health perspective. In Canada, Jason Kenney, the premier of my province, Alberta, was talking about the Calgary Stampede [the rodeo festival] as one of the first big events after the pandemic, as if the pandemic was over. Of course, those kinds of political declarations can have an impact on public perception and on policy, which can be harmful. They can have a polarizing impact on political discourse. One of the things I worry about with those kinds of pronouncements is that they’re going to feed complacency among those who either haven’t got a vaccine or are maybe thinking about not getting their second dose.

That said, it’s worthwhile to be positive. It’s important to give hope and to celebrate how far we’ve come. We’re just not finished. And so, how leaders present the end of the pandemic to the public really does matter. In parts of Canada, the U.S., and the U.K., this language has emerged to the effect of, It’s over, we’re through the tunnel. What happens if we have to reinstitute masks? What happens if we have to ask people to physically distance? It’s going to be tough to get compliance after leaders have told their populations that it’s over. That’s why it’s so important to make sure we frame the end properly.

How political leaders negotiate the end of the pandemic is going to have a big influence on how we all think about the end of the pandemic, especially since these things have become so politicized.

Bovy: Given the tremendous variation in case numbers and vaccination rates even within countries, would it possible to speak of the pandemic having ended in certain places, as long as other areas in the world are still in the grip of COVID?

Caulfield: From an epidemiological or public-health perspective, a particular region, may appear to be pandemic-free. But this is a global community. We need to think about the pandemic as an international phenomenon. It’s the proper way to think of it from a justice or equity perspective, but also from a scientific or public-health perspective. We don’t have walls around our every jurisdiction. The virus can spread very quickly.

How leaders present the end of the pandemic to the public really does matter. In parts of Canada, the U.S., and the U.K., this language has emerged to the effect of, “It’s over, we’re through the tunnel.” What happens if we have to reinstitute masks?

Bovy: Is a return to normal life the sign to look for? What specifically would be most definitive here?

Caulfield: I don’t think we’ll ever see a complete return to the pre-pandemic world. There will be subtle behavior changes with us for a long time. It’ll be interesting to see, for example, how many people in North America and Europe maintain mask wearing in certain settings. Will shaking hands, which is such a cultural institution, gradually come back as if the pandemic never happened? My prediction is no. I think we’re going to see more fist bumps and elbow touches.

Bovy: Will Europeans and others internationally still cheek-kiss hello?

Caulfield: That was going to be my next example. Or hugging. There’s so much that’s changed about the way we communicate, the way we teach, and how much we travel, that may all linger.

Bovy: Which age groups will likely be most and least affected over the long term by living through a pandemic?

Caulfield: The elderly cohort is likely to remain most affected. They were the ones that had the fastest uptake on the vaccines, understandably. They’re likely to remain very careful. The younger demographic, from 18 to 29, is the most complacent, with the lowest rates of vaccination. It’s the cohort that saw a tremendous impact on their education, and on the start of their careers. It will be interesting to follow the degree to which the pandemic shapes that cohort’s worldview. And for a younger demographic, there’s the impact on learning experiences, socialization skills, and mental health.

Bovy: Will there be any segments of the population, maybe along political lines, who continue to live as if in a pandemic, while the rest of the population moves on?

Caulfield: You often hear conservative commentators suggest that some on the left are going to live like they’re in a pandemic forever. My sense is that if those people are around, they’re a very small percentage. I work with people from across a wide range of disciplines and from different communities. I know nobody who holds to that view or wants to embrace a continued crisis mode. Have you seen it?

Bovy: What I’ve seen are people posting to social media, shaming others for behaviors like being outside in a park, which they find unseemly during a pandemic, but which aren’t actually risky in terms of how COVID is spread. It’s not that they’re living in the pandemic forever, but that they’re still following outmoded guidance.

Caulfield: That, I do see. It’s going to be interesting to see how people negotiate coming out of the pandemic. It’s necessary to balance the desire to be cautious with the reality that we are going to open up. And we shouldn’t shame people who are following public-health recommendations, who change behaviors once a particular public-health measure is no longer needed. We’ve been asked for so long to be vigilant, so it might be hard for some people to ease up and recognize when it’s time to go forward.

We need to think about the pandemic as an international phenomenon. It’s the proper way to think of it from a justice or equity perspective, but also from a scientific or public-health perspective.

Bovy: Understanding there will be no exact moment when things return relatively to normal, when might the end of the pandemic realistically happen?

Caulfield: The huge variable is the Delta variant. But for the Delta and the numbers of unvaccinated people, I would have been looking at feeling normal-ish by mid-fall. I’d like to believe it’s still going to be better in the fall. But if we’re talking about a complete eradication of concern about the spread of COVID-19, it could be fairly far off. The end of the pandemic will be a different story for the vaccinated and the unvaccinated.

Bovy: Many of the unvaccinated aren’t reluctant, as such, but simply too young to be in the age cohort approved for vaccination. As long as younger children can’t be vaccinated, can the pandemic really be over?

Caulfield: No, but I suspect we’re going to have a vaccine for everyone. Thankfully, clinical trials are happening. All-ages vaccination will be useful on so many levels, particularly in the context of community spread.

Bovy: Will it ever feel uneventful again to socialize indoors without a mask?

Caulfield: Human beings are incredibly accommodating, so I think this is going to happen. But we’ll be talking about how remarkable it is for another 5 or 10 years. Remember when we couldn’t do this? Those are the conversations I want to have.