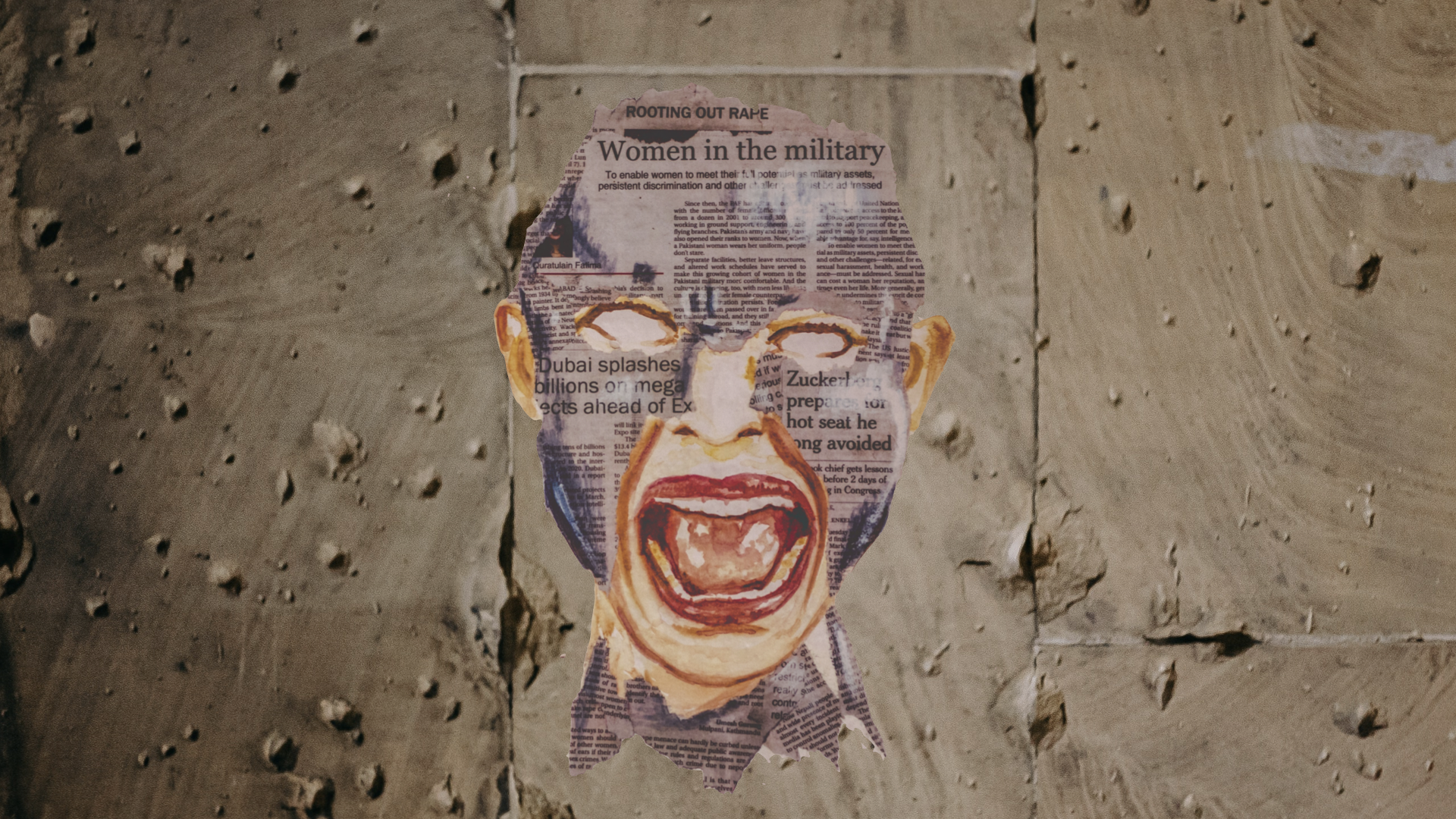

Some of the most intense political battles in America this year are taking place at school board meetings. Across the country, these meetings have become forums for intense debates, often among huge crowds, over whether to impose school mask mandates with the Delta variant of COVID-19 surging and how to teach the history of racism in the U.S. Those issues are already shaping local elections, where Republicans are channeling anger over mandatory masking and “critical race theory.” Last week, the Associated Press reported that a “loose network of conservative groups with ties to major Republican donors and party-aligned think tanks is quietly lending firepower” in these conflicts, which have occasionally resulted even in brawling and arrests. All this comes amid nationwide arguments over the idea that “woke” left-wing extremism is capturing American education, including at colleges and universities, and the issue of transgender-girl student athletes participating in girls’ sports. How are all these phenomena connected?

Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of the 2002 book Whose America? Culture Wars in the Public Schools, says schools are “the central public institution” where Americans “deliberate and decide what we want to communicate to our young people about who we are.” So he’s not surprised schools are such a locus of today’s culture wars. To Zimmerman, Donald Trump’s presidency intensified the fight over national identity in the U.S., not least over how it should be taught to students, which is part of why “the history wars”—the battles over how to understand America’s past—are “flaring as never before.” New narratives about the country, like The New York Times’ 1619 Project, aren’t just attempting to include marginalized voices in a traditional telling of America’s story, Zimmerman says; they’re attempting to question the story itself: “A lot of this new curricula reflects a fundamental challenge to the idea of America as a land of freedom and liberty.” At the same time, certain aspects of the education culture wars seem less contentious to him now than they have in the country’s recent history—particularly issues related to religious belief, such as teaching evolution or admitting school prayer.

Graham Vyse: Are schools now the central battleground in the U.S. culture wars?

Jonathan Zimmerman: They’re absolutely central. Sharp conflict over schooling is nothing new in America, but we’re at a new moment in the structure and content of that conflict. Back in 2002, I thought the religion wars had no solution and the history wars had the wrong one. The religion wars—over school prayer, evolution, and sex education inflected by religion—were insoluble, because they involved mutually incompatible claims. Either sex outside straight marriage is a sin or it isn’t. Either Christ died for our sins or he didn’t. Either we share DNA with other creatures or we don’t.

We did manage to solve the history wars, meanwhile, but I thought we solved them in the wrong way—just by adding new groups to the old story of America’s past. For a lot of our history, our textbooks were only about white men. Starting in the 1920s, and then really picking up during the civil rights era, we added more groups into the same story. Adding those groups was terrific, but we weren’t asking what adding they did to the broader story. Today, the history wars are flaring as never before, because there’s a real debate over the story itself. That’s what The 1619 Project is about—not just a demand for inclusion.

The religion wars have cooled radically. They haven’t gone away, but when was the last time you heard about a really brutal battle over school prayer or evolution in a community? It’s very rare. The people opposed to sex ed are now basically trying to get parents to opt out, meaning their kids don’t go when sex ed is offered. In a sense, that’s an admission of defeat, right?

Vyse: What are the stakes of these culture wars in the schools?

Zimmerman: The underlying stakes are nothing less than the definition of the nation itself. If you look at old textbooks, they have titles like Land of the Free. The 1619 Project questions the very premise: Are we a land of the free? At their root, these conflicts are about defining the United States as a nation, and public schools are the central public institution where we deliberate and decide what we want to communicate to our young people about who we are. In part, because the country is so fractured and polarized, it makes perfect sense that we’d be having this enormous battle in our schools. If you haven’t noticed, Americans don’t agree about America, and their disagreements may be as sharp as they’ve ever been.

The religion wars have cooled radically. They haven’t gone away, but when was the last time you heard about a really brutal battle over school prayer or evolution in a community? It’s very rare. The people opposed to sex ed are now basically trying to get parents to opt out, meaning their kids don’t go when sex ed is offered. In a sense, that’s an admission of defeat, right?

Vyse: Education was part of the national conversation in the Obama era, with a lot of discussion about school reform, but cultural conflicts in the schools didn’t seem as prominent as they do today.

Zimmerman: They’re heightened. I’m glad you mentioned Obama, because, in terms of “school reform”—which concerned the structure and financing of schools—there was an enormous consensus during the Obama years. There was consensus about [the federal education law] No Child Left Behind. There was a certain kind of consensus about “school choice.”

At the same time, the content of schooling—especially about the nation—was starting to become controverted and embattled, in part because of who Obama was and the way groups like the Tea Party rallied against him. At the state level, there were brutal battles over ethnic studies, especially in Arizona. You saw big battles in Texas over the history curriculum, especially church-and-state issues as well as the Alamo. Glenn Beck started “Founders’ Fridays” on Fox News, and he actually constructed a little one-room schoolhouse in his studio.

Vyse: The Tea Party movement began in 2009, avowedly in favor of smaller government and lower taxes but also, in part, clearly as a backlash to the first Black president and the cultural change he represented. It helped Republicans win a massive victory in the 2010 midterm elections. Now the Associated Press reports that some conservative activists see similar potential in the current education wars and are lending political support and organization to them. There’s even a lawyer quoted by the AP who says, “It seems very Tea Party-ish to me. … These are ingredients for having an impact on future elections.” What do you make of that?

Zimmerman: There’s something new about that. The article raises the “astroturf” issue: Is this actually a movement or the product of strategic work by people with some very deep pockets? It’s too early to say. There’s a similar debate about the Tea Party, the primary focus of which was the bailout, Obamacare, and taxes. People like Glenn Beck were very concerned about school curriculum, but that wasn’t the raison d’etre for the organization.

Vyse: Thinking about the specific issues at play today, what’s going on in the debate over “critical race theory,” “anti-racism” education, and the 1619 Project, which you’ve mentioned?

Zimmerman: Critical race theory has an academic genealogy. It comes out of work by mostly African-American scholars in law schools about 10 years after the Civil Rights Act, and they were asking a very fundamental question: A decade after all these laws banning racial discrimination, why is there still so much racial inequality? Their answer was that our institutions—including our legal institutions—have racism baked into them, so passing a single law saying you can’t discriminate in certain ways probably isn’t going to yield the outcome we want.

At their root, these conflicts are about defining the United States as a nation, and public schools are the central public institution where we deliberate and decide what we want to communicate to our young people about who we are. In part, because the country is so fractured and polarized, it makes perfect sense that we’d be having this enormous battle in our schools.

Is anyone “teaching” critical race theory in elementary and secondary schools? No. At the same time, it’s fair to say some of the ideas promulgated by critical race theory have entered these schools in some places—not under the banner of critical race theory but often under the banner of something called anti-racism. If your policy is that we have to dismantle systemic racism, you’re making a fairly profound claim about the United States—that it continues to be marked by systemic racism. It’s only in the past few years that we’ve seen school districts come up with policies like that. They’re fundamentally new, and they’re a challenge to the traditional account of U.S. history, which said that we had slavery and Jim Crow but are moving beyond all that.

Vyse: In the early Obama era, there was more of a sense among liberals and on the left that things were headed in the direction of racial progress.

Zimmerman: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Obama loved that quote from Martin Luther King Jr. so much that he had it sewn into a rug in the Oval Office.

Vyse: Still, many thinkers who’ve since risen to influence don’t share that sentiment. Ta-Nehisi Coates once wrote that he thought the arc of the moral universe “bent toward chaos.”

Zimmerman: That’s what’s different about our moment. For most of U.S. history, including during the Obama administration, liberals retained a kind of tenuous consensus on that arc of history metaphor: We’re not going to deny all the awful stuff, and it continues. But because America is America, we can fight against it and progressively (to use a loaded adverb) get closer to our founding ideals. That idea is under a certain kind of challenge, and Republicans are correct in their perception of that. But I’m not defending what they’re doing in response to that challenge [pushing bans on “critical race theory” across the country], which I find abhorrent.

Vyse: How are these fights over anti-racism and related subjects playing out in schools?

Zimmerman: Again, it’s too early to say. There are over 13,000 school districts in the U.S. Anyone who generalizes across them can be safely written off as an ideologue or a charlatan. We do know how this playing out politically. Many of these Republican censorship bills point to the psychological dangers these new curricula allegedly pose, ostensibly because they make people feel bad or guilty.

This is a tremendous teachable moment, and I’m afraid we won’t leverage it. Since these new perspectives represent a fundamental challenge to the traditional story of America, we should be putting these stories next to each other in our schools and having our students conduct the debate we’re conducting outside schools. Some teachers do this, but not many. There isn’t enough of a constituency for it.

Critical race theory has an academic genealogy. It comes out of work by mostly African-American scholars in law schools about 10 years after the Civil Rights Act, and they were asking a very fundamental question: A decade after all these laws banning racial discrimination, why is there still so much racial inequality? Their answer was that our institutions … have racism baked into them, so passing a single law saying you can’t discriminate in certain ways probably isn’t going to yield the outcome we want.

People want to see their point of view privileged. They want all the kids to know America is a systemically racist place or they want all the kids to know it’s a beacon of freedom and progress. But both of those views represent species of the same problem, which is that we don’t have enough faith in our schools—or our kids—to let them sort these questions out on their own.

Vyse: How has this been politicized?

Zimmerman: The Republican media machine has weaponized critical race theory. At one point, [the right-wing activist] Christopher Rufo said he wanted every community in America to be afraid of critical race theory. It’s incredibly cynical. It’s also very effective.

[“We have successfully frozen their brand—‘critical race theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category,” Rufo wrote on Twitter in March. “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’”]

Vyse: What about the fight over transgender athletes in girls’ sports? Why has that become a big issue?

Zimmerman: I actually think it hasn’t been as big an issue as a lot of Republicans wanted it to be, precisely because battles over religion and religious values—which are closely connected to these transgender issues—have cooled. Trump rescinded the Obama administration’s order that schools had to allow kids to choose whatever bathroom they wanted to use, but then states began to pass bathroom bills and there was such an uproar, with threats of corporate boycotts, that both North Carolina and Texas backed off immediately. We’ve just gone through a cycle where we saw thousands of people converge on school boards with placards and banners—all about race and racism. That never happened with the transgender question.

Vyse: Was there a primary aggressor in this current round of school-based culture wars?

Zimmerman: It’s a hard question to answer. If you look at the history of the culture wars, the aggressor has always been the person objecting to some new or troubling feature of the curriculum. Fundamentalist Christians correctly perceived a threat to some of their religious stories in Darwinism. In the 1950s and 1960s, African-Americans and other racial minorities correctly perceived that some textbooks communicated racism. The NAACP and the Urban League had textbook committees, which went into school districts, looked at what they were teaching, and objected to white-supremacist stories being told.

People want to see their point of view privileged. They want all the kids to know America is a systemically racist place or they want all the kids to know it’s a beacon of freedom and progress. But both of those views represent species of the same problem, which is that we don’t have enough faith in our schools—or our kids—to let them sort these questions out on their own.

It seems to me that the Christopher Rufos of the world are clearly the aggressors today. They’ve weaponized this issue, because they perceive correctly that there’s something new about the way we’re presenting questions of nation and race in our schools.

Vyse: They’d say that the people pushing those new ideas are the aggressors—teaching that America is a white supremacist country, for example, in a way that wouldn’t have been taught a decade ago.

Zimmerman: Fair enough. In that analysis, maybe Ibram X. Kendi [the author of How to Be an Antiracist] is the aggressor, because he and his followers are saying, Enough of saying the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice. Let’s look at what’s “stamped from the beginning,” which is the title of one of Kendi’s books. Let’s look at how things really work, repeating the same story over and over again—a story of racist oppression. Trump and his explicitly racial and racist language gave more credence to the claims of people like Coates and Kendi.

Vyse: There are a number of culture-war issues stemming from college campuses—anxieties over “cancel culture,” the idea that there’s a diminishing commitment to free speech on the left or a rising left-wing illiberalism in certain corners. What’s happening around those issues?

Zimmerman: Something we’ve discovered is that we do a very poor job in the U.S. of teaching our kids, at the K-12 level, how to speak across difference. Our students often arrive in college having no experience whatsoever in classroom settings in how to conduct a political discussion. Should we really be surprised that there’s so much brittleness and fear and self-censorship at the college level?

Vyse: Another culture-war issue centered on schools at the moment is mask wearing in the pandemic. How does that relate to the issues we’re discussing?

Zimmerman: One thing you see in culture wars, including those we’re talking about related to history, is a rejection of expert authority. The mask matter embodies that better than anything else.

Vyse: Are culture wars over schooling in any way part of a global phenomenon?

Zimmerman: The question of national identity is being debated in schools around the world, but most of those schools have national education systems that America doesn’t have. There’ve been enormous battles in France recently over the meaning of the French nation and what to teach about the French colonial experience, for example.

There’s always going to be variation depending on the history and culture of a country, but one reason these culture wars are a little more powerful in America is that Americans have a stronger sense of their own exceptionalism in the world. They’re more likely to think of themselves as being at the forefront of that arc of history. Now, polling shows a decline in the number of Americans who say we’re the greatest country on earth—it’s still a majority, but not what it used to be. Still, Americans have generally had more invested in their own place in history, so a lot of these questions have been more emotional and contested.