‘Deplorable’

Across America, once-prosperous towns have fallen into neglect. Gary, Indiana, has lost half its population over the last 50 years. U.S. Steel’s Gary Works, which employed some 30,000 in the 1970s, now has only a little more than 2,000 workers. The trains no longer stop at Gary’s Union Station. Neighborhoods where families used to live have been completely abandoned. School after school has been closed. Life, of course, goes on—but there’s less of it.

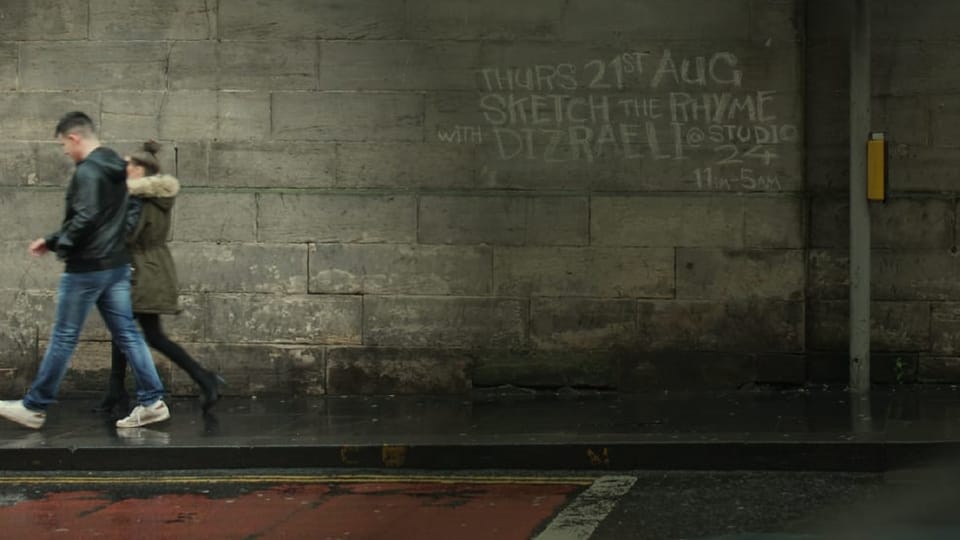

In Europe, meanwhile, regional inequality has been increasing since the 1980s, but far more so in some countries than in others. Britain, for example, is an extreme case. The South East is rapidly pulling ahead of the rest of the country, especially the North East, where the median household wealth is lower today than it was in 2006.

But while some places keep falling behind, others have caught up. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, lost huge parts of its heavy steel industry in the second half of the twentieth century. People started leaving, to the point that the city lost half its total population. For a while, it looked as though Pittsburgh would never recover, but today, it’s one of America’s most successful and innovative cities.

But in other places in the U.S., the U.K., and around the world, regional inequality is only becoming more pronounced. Between 2010 and 2020, the average wealth gap between people in England overall and the North almost doubled—and it keeps growing. Why are these places falling further behind?

Sir Paul Collier is a professor of economics and public policy in the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University, the Oxford academic director of the International Growth Centre of Oxford University and the London School of Economics and Political Science, and the author of Left Behind: A New Economics for Neglected Places.

Collier says it’s perfectly normal for economically neglected regions to recover, but where they’re not—where they’re falling further behind—it’s often because they’re in countries where the central government has overly concentrated its power. Policy makers in capitals often care little about their countries’ peripheral towns, cities, and regions; know about them even less; and even when they do, often end up paralyzed by bureaucratic infighting and inertia.

So why have some places managed to recover? We can find clues, Collier says, by looking to cases like the Basque region of Spain, which has gone from being one of Europe’s poorest and most violent regions to one of its most attractive. That recovery wasn’t powered by Spain’s leaders in Madrid but by Basques themselves. And giving locals the means to solve local problems hasn’t just worked in the Basque region but in place after place. Which raises the question of whether and how central governments will be willing to give local authorities real political power ...

Gustav Jönsson: What countries do you see having especially stark regional inequality?