Requiem for a slogan

In November 2012, soon after becoming general secretary of the Communist Party of China, Xi Jinping gave a speech in Beijing describing the “Chinese Dream.” It would go on to become the defining catchphrase of his presidency.

Schools and universities across the country created “dream walls,” encouraging students to write down their goals. They organized dream-speaking competitions. Students’ ambitions ranged, but many aspired to the same things: a stable job, a reliable income, and the chance to make a better life than their parents’.

Their aspirations would fuel the nation’s. Xi said the Chinese Dream was “realizing a prosperous and strong country, the rejuvenation of the nation and the well-being of the people.” All this would happen, he said, by the middle of the century.

Instead, the dream has become a chimera. Opportunities for China’s youth have stagnated, and China’s middle class is disappearing. Household incomes have flatlined. Youth unemployment hit a record high of 21.3 percent in 2023. The same year, more than 70 percent of unemployed young people in cities had a degree. They call themselves “rat people” and “rotten-tail kids”—college grads in low-wage work or living with their parents. There are more and more of them. The malaise has spawned the “lying flat” movement—a rebellion against punishing hours and eternal struggle with few rewards.

What went wrong?

Yi-Ling Liu is a journalist in residence at the Tarbell Center for AI Journalism and the author of a forthcoming book on the Chinese internet. She says the energy that once defined China’s economic rise—the tech boom, the surging middle class, the expansive sense of possibility—has ebbed. The economy has stalled. Innovation has stalled. Real estate is in crisis. Where relentless striving was once the norm, young people are now opting out.

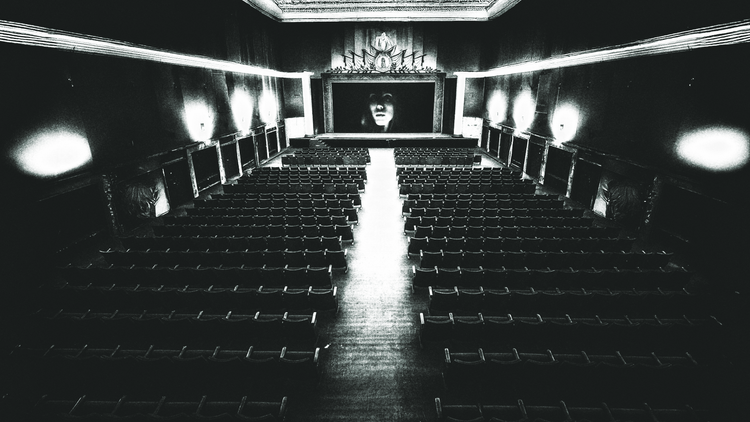

Ambitious goals on dream boards have given way to disillusioned posts online. The Chinese internet, Liu says, once felt like a frontier—a space of possibility, creativity, and connection. Now, like everything else, it feels increasingly closed off. But in a country where public protest is rare, it’s still a crucial outlet—and the source of a new language of apathy. During the pandemic, a phrase capturing the national mood went viral on the Chinese internet: “We are the last generation.”

Allison Braden: Since Xi Jinping coined the term in 2012, the Chinese Dream has been notoriously hard to define. How do you understand it?