Declarations of independence

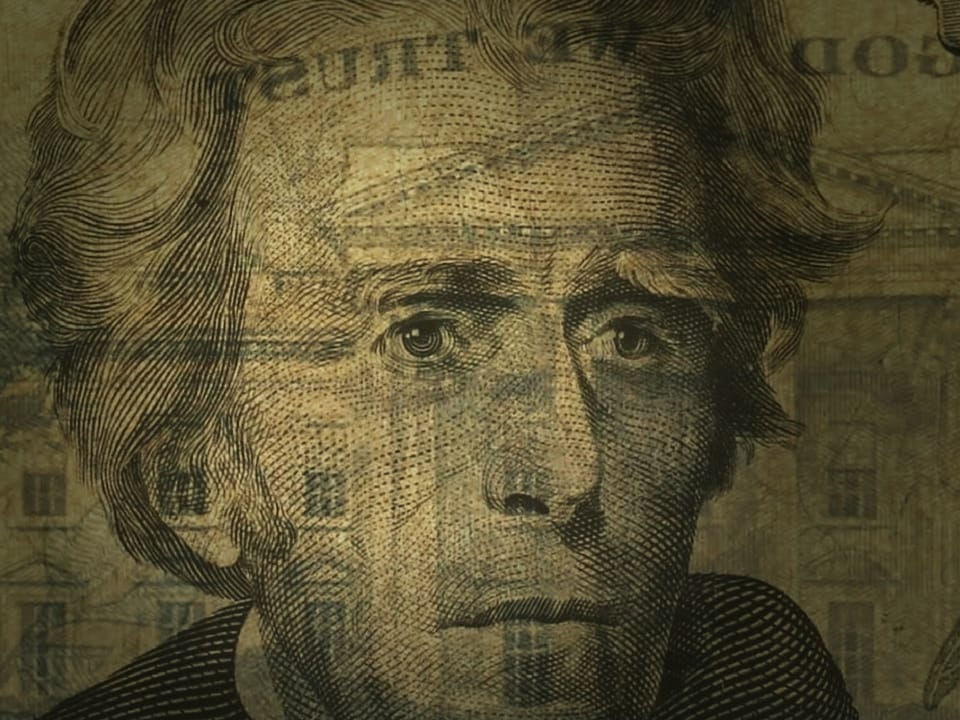

The president of the United States is not pleased with Jerome Powell, the chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve. Donald Trump has called him “terrible,” “stupid,” “a stubborn mule,” and “a total and complete moron.” The proximate cause of Trump’s irritation is the Fed’s reluctance to lower borrowing costs, which have hovered between 4.25 and 4.5 percent this year. Were it not for the president’s tariffs, Powell said last month, the Fed would most likely already have lowered rates. Powell, Trump countered, has “cost the U.S.A. a fortune.”

Now, Trump is threatening to fire Powell before his term has ended and replace him with someone more politically pliant. This would of course undermine the Fed’s independence, which has historically kept monetary policy at a distance from electoral politics.

Neither is Trump the only politician on the contemporary right criticizing central-bank independence. In the United Kingdom, the insurgent Reform Party recently said it’ll consider whether the Bank of England should be stripped of its independence. In Turkey last year, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the self-styled “enemy of interest rates,” clashed with the country’s top court over his right to fire central-bank governors, having removed five of them in the preceding five years. In Thailand, the ruling Pheu Thai Party is seeking greater control over monetary policy. And in Poland, the populist-right party Law and Justice has installed Adam Glapiński as president of the National Bank of Poland, who just so happens to be a long-time friend of the party's leader Jarosław Kaczyński. Earlier this year, the president of the European Central Bank, Christine Lagarde, said central-bank independence is “now coming under increasing pressure.” It was modal European-bureaucratic understatement.

Why is this all happening now?

Stefan Eich is an assistant professor of governance at Georgetown University and the author of The Currency of Politics: The Political Theory of Money from Aristotle to Keynes. Eich says Trump’s hostility to high interest rates goes all the way back to the 1980s, when he was a real-estate developer in New York and rates were much higher than they are today. That experience left him ideologically committed to low interest rates. And of course, lowering rates might be politically advantageous to him as it would, at least in the short term, give the American economy a boost.

But there’s more to it than that. Ever since the financial crisis of 2008, people around the world have become increasingly aware of the power of central banks to intervene in the financial system. They’ve also become more aware of that these interventions can have clear winners and losers. During the financial crisis, the U.S. Federal Reserve bailed out banks but not homeowners, many of whom then lost their homes to foreclosures. Meanwhile, central banks face next to no democratic scrutiny; their board members have been selected, not elected. It seems discontent with that system is becoming a real political theme. Which brings with it the question: Can central banks be democratically accountable without becoming the plaything of whoever happens to be in office?

Gustav Jönsson: Exactly what do we mean by central-bank independence?